“Jennifer, can I give you some constructive criticism?”

“Sure”

“Try using your brain.”

— Conversation with my boss, circa 2002

I have shared this conversation many times to big laughs over the years. But only since becoming an evangelist for RADICAL CANDOR, the leadership and feedback model created by Kim Scott, have I revisited it and understood it for what it really was: a legitimate criticism given in the context of a trusting professional relationship.

Although her words may have sounded harsh to an outsider (and I’m not advocating for using this particular comment with your team members), I had a relationship with this person so what I heard (and what I knew my boss meant) was, “You’re phoning it in. This work doesn’t reflect your full abilities and I know you can do better.”

At that time, my boss Jane ran the fundraising department for New York City Opera and we had worked together for seven years. She had plucked me from an administrative job, explained to me that I was destined to be a fundraiser, and promoted me into increasingly challenging roles I was convinced I couldn’t do. During those years I learned that Jane often saw in me potential that I didn’t see in myself. She pushed me beyond my own boundaries and she let me know when I wasn’t living up to expectations. In other words, she cared personally and challenged directly; without knowing it, Jane was practicing Radical Candor.

Scott, who cut her teeth at Google and taught a course for Apple University called “Managing at Apple,” always dreamed of creating a better corporate culture. Her Radical Candor model contends that if we care personally enough about our colleagues – truly making relationships with them and being invested in their success – we build up a reserve of trust that earns us the right to speak directly to one another. That means being able to give praise and criticism in a direct way – to our team members, our colleagues, and even our boss – as soon as an issue arises, and not hold onto it until a weekly meeting or a quarterly review.

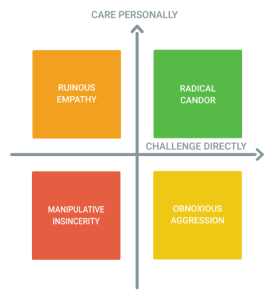

The model situates “caring personally” and “challenging directly” on two axes which create 4 quadrants (see below). If you are doing well in both caring and challenging, you fall into the upper right quadrant of radical candor, but the model also exposes the unacceptable alternatives:

- If you’re low on the care personally axis but high on the challenge directly axis, you’re in the obnoxious aggression (That’s the team member who bangs his fist on the desk to make a point.)

- If you’re high on caring personally but low on challenging directly you’re in the ruinous empathy (That’s the boss who in an attempt to be “nice” can’t give you the criticism you need to do your job well and ultimately winds up firing you without warning.)

- If you’re low on both axes you’re in the worst quadrant of all: manipulative insincerity. (This is where the most toxic, political and passive-aggressive behavior lives.)

Any of this sound familiar?

Radical Candor is about more than feedback; it’s about culture. Imagine a workplace where there is no space for office politics and backstabbing because the culture invites you – in fact, requires you – to speak up, speak often, and speak truth to power. Imagine being in constant dialogue with your boss and colleagues about what you’re doing well and where you need to grow; how would it feel to walk into your boss’ office for your annual review?

Create a culture where everyone knows criticism is about helping each other do the best work of their careers.

It’s not mean. It’s clear.

–Kim Scott

But how do we put this into practice?

For Scott, it starts at the top. The most important thing a boss can do is focus on guidance – giving it, receiving it and encouraging it. But she knows this isn’t as easy as it sounds. From as far back as we can remember, our parents taught us that “if we don’t have something nice to say…” Being a boss means undoing that training and leaning in to the idea not just of giving criticism but of asking for it – and not just asking for it, but demanding it. By doing this, we start to create a culture with a multi-directional flow of caring, challenging and truth-telling.

What is the impact of such a culture?

In Scott’s words, “While it seems safer just to remain silent, it’s not safe. It’s depressing.” Rather, when everyone starts to understand that instead of engendering negative consequences for speaking up there is encouragement and support, they start to share their challenges and failures. The result? An environment in which people learn that it is safe to fail, which in turn fosters more risk-taking and greater innovation.

And when I think back on my days with Jane, I now have a framework to understand why she was in fact the greatest boss I ever had – something I never would have figured out without using my brain.

Interested in learning more about Radical Candor for your organization? Check out these resources:

https://www.radicalcandor.com/the-book/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4yODalLQ2lM